Figure 1. Nilgai (females in the back of photo) are much larger than whitetail deer (female in front). Photograph by Timothy E. Fulbright.

Dietary Competition among Nilgai, Cattle, and Deer: What We Can Learn from Atoms

By: Stacy L. Hines, Timothy E. Fulbright, J. Alfonso Ortega-Santos, David G. Hewitt, Thomas W. Boutton, and Alfonso Ortega-Sanchez, Jr.

Many south Texas ranchers rely on income from a combination of cattle and wildlife enterprises. Sustainable management of domestic and wild animals is an intricate balancing act in which animal population densities must be balanced with available forage.

Damage to plants by foraging animals, resulting from too many critters competing for the same forage, reduces the number of animals the land can support in the future. Profits suffer when animal production declines.

Management of multiple animal species is based on knowing what plant species animals eat and recognizing the potential for competition among species.

Several different methods have been used in the past to determine the amounts and kinds of plants that animals consume and to determine the plant species they prefer to eat. Each of these methods have different flaws.

One popular approach, for example, has been to collect samples from animal stomachs, and then identify the plant species in the sample. You can imagine how difficult it is to identify plant fragments that are partially digested!

Based on these methods, researchers have classified white-tailed deer as browsers, animals that primarily eat leaves and twigs of woody plants. Cattle are grazers, animals that eat mainly grass.

Nilgai are a large antelope species from India that were introduced into south Texas during the 1930’s. The estimated population of nilgai in Texas is about 15,000 animals. Nilgai have been classed as grazers or intermediate feeders, animals that can eat grass, browse, and broad-leaved weeds that biologists refer to as forbs.

In one study, nilgai consumed a diet of 60% grass, 25% forbs, and 15% browse. The results of the study indicated that they have a high potential of dietary overlap with cattle, but much less overlap with white-tailed deer.

How we use stable isotopes?

Use of stable isotopes to determine diet overlap is relatively new. Isotopes are simply forms of the atom of a chemical element that vary in the number of neutrons. Everything is made of atoms. Once forage is consumed, the atoms comprising the forage are absorbed and used to make animal tissues.

Therefore, the stable isotope signature of animal tissues and feces reflects the composition of the atoms that comprised the forage consumed. Differences in dietary preference can be detected if plants that are eaten have different isotope signatures. Analysis of atoms eliminates flaws associated with other methods, such as stomach content analysis.

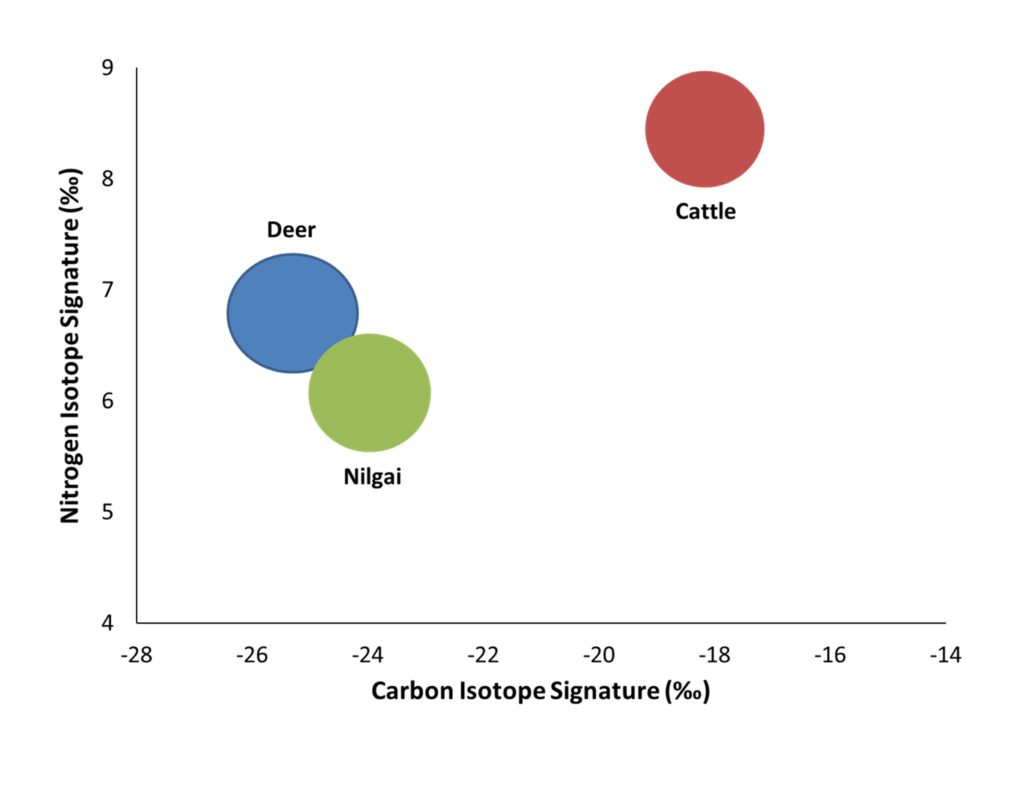

We analyzed the stable isotope signatures of nilgai, cattle, and deer feces on six study sites on East Wildlife Foundation lands across south Texas during the peak of the growing season in autumn 2012.

In addition, at each study site we analyzed the stable isotope signature of plant species that were reported to be highly preferred by nilgai, cattle, and deer in other studies from south Texas. We found that grass and forb species in south Texas have distinct isotope signatures. Nilgai were present at three of the six sites and their diets, in contrast to the results of past studies, did not overlap with cattle.

Deer and nilgai diets overlapped strongly at all three sites, the opposite of what we expected based on past research. At five of the six study sites, cattle and deer diets did not overlap, but there was substantial overlap at one site.

The ‘take home’ messages based on our results thus far are:

⦁ Nilgai consume less grass than previously thought and compete little with cattle for food.

⦁ Nilgai compete directly with white-tailed deer. Rangeland where nilgai are present will not support as many deer as rangeland with no nilgai.

⦁ Cattle diets are unlikely to overlap with nilgai or deer when there is grass available.

⦁ Cattle and deer diets overlap when forbs and grasses are deficient.

⦁ We will continue data collection for three years to see if our results change with varying weather conditions and seasons.

Stable isotope analysis is a relatively new approach in animal foraging studies. Examining the stable isotope signature of animal tissues to determine diet overlap eliminates flaws associated with previous research methods. We are excited about applying this technique to wildlife studies in Texas.

Also, we are refining the technique to make it more applicable across lands in Texas. We are currently using isotopes of carbon and nitrogen. We have plans to explore potential use of other elements to help us improve and refine our ability to identify plant species that occur in animal diets in Texas.

Our research is one component of the East Wildlife Foundation’s charitable research program. Through research, education, and outreach the East Wildlife Foundation supports “wildlife conservation and other public benefits of ranching and private land stewardship.”

We also thank the Houston Safari Club for providing a scholarship to support Stacy’s education.